3 December 2016 – Mellon Sawyer Seminar Hands On Session

PAPYRUS PRODUCTION

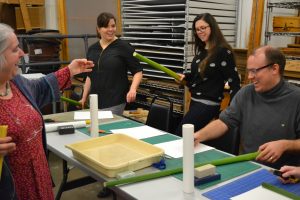

Papyrus making and Chinese scroll production were on the docket for the Mellon Sawyer December Hands On workshop. Myriam Krutzsch, papyrus conservator at the Aegyptisches Museum [Berlin] started the day off with a brief intro to papyrus production at the UI Center for the Book’s papermaking studio.

Papyrus is a reed plant common to the Nile River Valley. It was produced there as early as the 4th century BCE, and exported extensively throughout ancient Rome, especially after Rome’s conquest of Egypt in the 1st century BCE. It can be cut at the base and will quickly grow back, making it a renewable ancient resource. The brushy tops are cut off and stalk cut into shorter lengths for processing. The plant can grow to be more than 15 feet in height, thus providing a great deal of raw material.

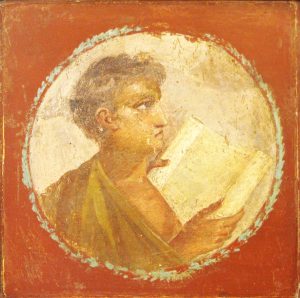

By the 5th century CE, papyrus was being overtaken by parchment [animal skin] as the preferred sheet material [at least for use in codices – perhaps because it was a stronger material to bind/sew through?]. Despite the growing dominance of parchment, there is evidence that papyrus was in use well into the Middle Ages in Merovingian and Byzantine chanceries – long after it was superseded by parchment as the preferred sheet material. It would be interesting to see a quantitative codicological study on the appearance and use of papyrus throughout the Middle Ages. When it was used alongside parchment, what texts was it chosen for, when, in what region and under what rulers? Like the choice to use a scroll form for medieval decrees and rabbinic texts such as the Torah, even after the advent of the codex, the late use of papyrus likely referenced ancient authority and a kind of authenticity that was associated with the material itself. Papyrus, in the Middle Ages, may have referenced the power and authority of ancient Rome and perhaps even its conquest of ancient lands, such as Egypt.

Like most things, papyrus making is easy to do, hard to do well. The Mellon Sawyer seminar and Center for the Book have been involved in a number of attempts to recreate historical production practices in order to understand how early materials, such as medieval paper and parchment, were produced and used. Understanding materials helps us understand how texts were created, how book forms and scripts evolved and how manuscript technologies [and thus religions and book cultures] spread throughout the premodern world.

Krutzsch and her pupils, Classics grad students Caitlyn Marley, Echo Smith, Mellon Sawyer PI Paul Dilley and Peter Miller [laughing about a joke in Old Nubian?]

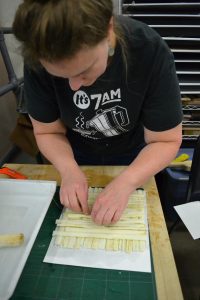

Myriam Krutzsch patiently guided participants through the steps involved in taking papyrus from stalk to sheet. Papyrus production basically consists of cutting the plant at the base and top, then cutting the stalk into sections. The outer skin of the reed is stripped. We used an Olfa knife/ small utility knife for this.

It is important to soak the stripped stalks and keep them moist until you are ready to split them in to strips.

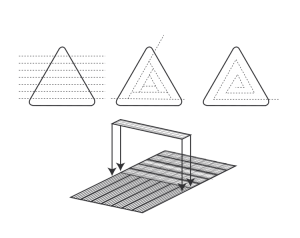

To create flat strips, strips can be cut from the stalk [the ‘Classical method’, above left and center] or the stalk can be peeled radially so that one is left with a continuous width of flattened papyrus [the ‘peeling method’ above right]. We followed Pliny’s lead and used a needle for this step.

The workshop was not without levity. Amy Holmes-Tagchungdarpa joked that her style of papyrus making was Late, Late, Late Kingdom Egyptian. William Johnson, an expert on classical literary rolls – who was carefully assembled his papyrus sheet – noted that his was for shoes.

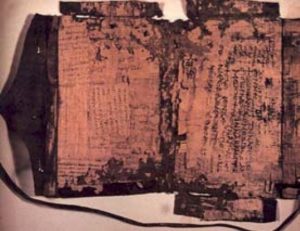

Strips include the pith, the soft inner strata of the papyrus stalk. Strips are then laid next to one another vertically and another course laid on top horizontally to create a sheet. These two perpendicular layers create the papyrus sheet. The horizontal strips become the recto side of the papyrus sheet/roll – made ready for horizontal writing. The vertical strips become the verso side. Krutzsch noted in her lecture that the recto of ancient papyrus was always the finer side – probably because this was the writing side and had to be smooth and consistent in quality and texture. She also notes that, in general, papyrus got thicker throughout the centuries – with marked thickness occurring in the Greco-Roman period when the change writing tools [from a softer to harder tool] necessitated a thicker sheet material.

After the recto and verso sides are laid out, sheets are pressed by rolling with a pin and/or pounding lightly with a large wooden mallet to facilitate the bonding of the two layers together. Sheets can then be pressed under heavy weight. Pressing activates the natural cellulose in the plant which acts as a glue, adhering the two perpendicular layers together. We used a large book press and a hydraulic papermaking press to press the sheets, which were stacked with a lightweight interleaving material to prevent them from sticking together.

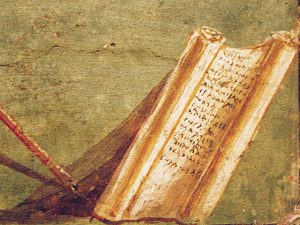

Sheets are then dried flat between blotters. Once dry, individual sheets can be joined together to form a long roll or scroll. This step would have been done in the papyrus workshop in the case of ready-made rolls, but the scribe could also join rolls together and/or add extra sheets to the end or beginning of their roll if the text necessitated it.

During Mellon Sawyer workshop, participants cut, split, peeled, rolled and pressed sheets of papyrus. Our papyrus was sourced from a nursery in Florida as Cyperus Papyrus, cut fresh and shipped overnight. Though it was the proper species of plant, it may have been an ornamental variety, as it didn’t have the cellulosic sticking power that I have experienced in the past with papyrus. Sheets didn’t stick together as well as they might have. Myriam Krutzsch had not had this issue in previous workshops, so it was apparently due to the source [perhaps this ornamental variety] or perhaps the freshness of the stalk. Makes one appreciate good Nile River Delta papyrus! The quality and specificity of raw materials are critical. We experience this each time we attempt to step back into the shoes of an ancient or medieval craftsperson. The challenges of learning about how early manuscript materials were made are always twofold – hand skills are one issue, raw materials the other [See UICB attempt at making 2000 sheets of paper in one day].

At the end of the workshop we used writing-ready sheets of papyrus, shipped from Egypt to construct two papyrus rolls with different types of joins. Joins are the places where the individual papyrus sheets are attached together to form a finished roll/ scroll. Myriam Krutzsch, through decades of diligent conservation of thousands of ancient papyri, has developed an extensive typology of these papyrus joins [see her Mellon Sawyer lecture on this topic here]. Identifying the type of join can provide valuable information on the place and period of production. There were standard techniques of joining sheets together – indicative of certain workshops, places and periods. Join analysis can also reveal information about who compiled the roll – a workshop craftsman or scribe. Krutzsch divides joins into three categories: ‘manufacture joins,’ those done in the workshop with consistent lap direction [one sheet laid over the other the same way all along the roll]; ‘scribe joins,’ those done by the scribe before, during or after writing – here either individual sheets or whole rolls are joined together with inconsistent lap direction [because it’s a d.i.y. job]; and ‘office joins’ where already completed, scribed documents are joined together with inconsistent lap direction [and inked letters sometimes covered by the join]. She notes that the width of the join increased through the centuries, from .5 cm joins in Old Kingdom Egypt [2700 to 2000 BCE] to 3 cm joins by the Byzantine and Arabic Period. Krutzsch has recorded joins of 2, 3, 4 and 5 layers, various widths, sheets of various color, thicknesses and quality, indicative of certain places and periods of production from Old, Middle and New Kingdom Egypt, through the Greco-Roman, Byzantine and Arabic periods. I wonder if any of this substrate information will become available from the new techniques being developed by computer engineer Brent Seales and physicist Vito Mocella – who are now in the middle of a project involving the digital unwrapping of ancient Roman rolls from Herculaneum. Of course the textual information from the Herculaneum rolls are of primary importance, but getting some information about the papyrus substrate would add to the information we will have about how and where these rolls were produced.

CHINESE SCROLL PRODUCTION

The production day was divided between papyrus production and ancient Chinese scroll production, led by Mark Barnard. Barnard was the head of Paper Conservation at the British Library and conserved, among other things, the fragile, 9th-c. Diamond Sutra – the oldest known printed dated book in the world [no pressure!].

After a morning of pounding, rolling and pressing papyrus sheets, the group was treated to a tea break, followed by an introduction to ancient Chinese scroll production by Barnard. This included a discussion of tools, brushes, paper, and a demonstration of how to make calligraphy ink from a stick. We then tried our hand at Chinese calligraphy, with brush and ink, using sheets of practice paper and a cheat sheet of brush strokes and Chinese characters as an aid. Chinese flute music set the tone for the afternoon.

Participants worked carefully on their Chinese calligraphy, with helpful suggestions from Susan Whitfield and UICB calligrapher Cheryl Jacobsen. The calligraphy session was deeply relaxing and allowed us to refocus our energies on the task at hand – assembly of our Chinese scrolls.

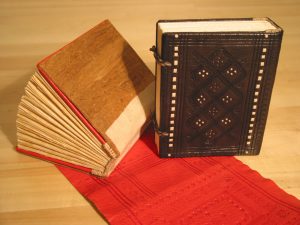

Barnard demonstrated how to assemble the scrolls. Covers were made from a double weight paper which was rolled/ glued around a thin dowel with a strap laced through a recess at the edge.

The main body of the scroll was trimmed down from a larger sheet of Japanese paper which was then tipped [glued with a thin overlap] onto the cover. A thick dowel was attached to the end of the paper scroll. The final scroll was then ruled with vertical guidelines.

Melissa Moreton